Could Stress be Contributing to Your Client’s Resistance to Weight Loss?

September 25, 2021 2024-01-03 13:51Could Stress be Contributing to Your Client’s Resistance to Weight Loss?

Could Stress be Contributing to Your Client’s Resistance to Weight Loss?

By: Lisa Tsakos R.H.N. and Heather Creamer R.H.N. (including excerpts from the Natural Nutrition Coach® Certificate program)

Modern life is fraught with stress. The impact that the covid virus has had on our daily life, combined with the regular pressures of life—finances, family responsibilities, health problems, and work demands, to name a few—it can be overwhelming for many. The very devices created to make life easier, such as technology, mobile phones, and the internet, have instead resulted in a faster pace, more demands, minimal downtime, and overstimulated minds. Generally, humans today are overloaded with STRESS!

Stress takes a toll on health, and that toll can have life-long consequences. It is now recognized that the greatest causes of death and disease on the planet are preventable lifestyle-related chronic diseases.[1] Stressful situations may cause people to eat more, stop exercising, consume more sugar, caffeine or alcohol, turn to drugs, and engage in other destructive behaviours. Prolonged exposure to stress can cause imbalances in a person’s mental and physiological state, leading to depression, high blood pressure, heart disease and metabolic disorders. It should not be surprising to you, then, as a Fitness Professional, to find that the health effects caused by stress will be among the most frequently mentioned concerns expressed by your clients and should also be considered as a factor when clients plateau or are having difficulty trying to lose weight, even when they are doing “all the right things”!

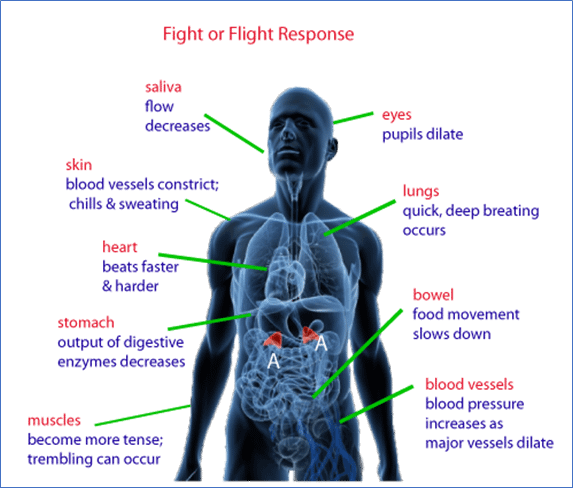

How Stress Works in the Body: The Fight or Flight Response

When the brain perceives a situation as stressful, a cascade of stress hormones produces well-orchestrated physiological changes in the body. This reaction is known as the “fight-or-flight” response.

This response evolved as a survival mechanism, enabling humans and other mammals to react quickly to life-threatening situations, like being confronted by a wild animal. The immediate hormonal changes and physiological responses helps the person shift gears to stay and fight the animal (“fight”) or flee to safety (“flight”). Nowadays, the stressors most people experience are not life-threatening, but work deadlines and traffic jams, elicit the same response from the body.

Over time, repeated activation of the stress response takes a toll on health. Research suggests that chronic stress contributes to high blood pressure, promotes the formation of artery-clogging deposits, and causes brain changes that may contribute to anxiety, depression, and addiction. Chronic stress may also contribute to obesity, both through direct mechanisms (e.g., stress hormones can cause someone to eat more or to make poor eating choices) or indirectly (e.g., stress can interfere with sleep and exercise).[2]

Source: American Institute for Stress America’s #1 Health Problem – The American Institute of Stress

The stress response begins in the brain. Let’s say a car is driving out of control and in your direction. Immediately, the amygdala of your brain (the area of the brain that contributes to emotional processing) interprets the situation as dangerous and sends a distress signal to your hypothalamus, the area of the brain that communicates with the rest of the body through the autonomic nervous system. This system controls the fight-or-flight response, as well as involuntary body functions including breathing, blood pressure, heartbeat, digestion, respiratory rate, urination, and sexual arousal.

The autonomic nervous system has two components, the sympathetic nervous system, and the parasympathetic nervous system.

- The sympathetic nervous system triggers the “fight or flight response”, providing the body with immediate energy to respond to perceived dangers.

- The parasympathetic nervous system promotes the “rest and digest response” that calms the body down after the danger has passed.

The HPA axis

The hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system by sending signals through the autonomic nerves to the adrenal glands. These glands respond by releasing the hormone adrenaline (also called epinephrine) into the bloodstream.

The hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system by sending signals through the autonomic nerves to the adrenal glands. These glands respond by releasing the hormone adrenaline (also called epinephrine) into the bloodstream.

As adrenaline circulates through the body, it causes numerous physiological changes—the fight-or-flight response. This response occurs so rapidly, often the person it’s happening to, is not even aware of it, yet somehow reacts (for example, moving out of the way before the out-of-control vehicle hits you).

The hypothalamus then activates the second component of the stress response system known as the HPA (hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal glands) axis. The hypothalamus secretes the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which travels to the pituitary gland, triggering the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). This hormone travels to the adrenal glands, prompting them to release the adrenal hormone, cortisol (hydrocortisone). Cortisol keeps the body on high alert until the threat passes. Once the threat has gone away, adrenaline and cortisol levels should subside, the parasympathetic nervous system inhibits the stress response, and the body’s responses return to normal.[3] But with chronic stress the ability for the parasympathetic nervous system to be activated itself becomes inhibited. [4]

Cortisol Contributes to Weight Gain

Cortisol levels remain high when the parasympathetic nervous system isn’t activated! Cortisol creates physiological changes that help to replenish energy stores that were depleted during the stress response. This is useful following a famine, or if someone is training for an endurance sporting event, but for the average person, it can be damaging. For example, during prolonged stress, cortisol increases appetite, enticing people to eat more. The weight gain occurs in the mid-section.[5]

Beyond Weight Loss- Chronic Elevation of Cortisol increases Health Risks

Persisting high levels of cortisol contributes to the development of insulin resistance, hypertension, abdominal obesity, and elevated triglycerides and cholesterol.[6]

Persisting high levels of cortisol contributes to the development of insulin resistance, hypertension, abdominal obesity, and elevated triglycerides and cholesterol.[6]

Abdominal, or visceral fat, is of more concern than subcutaneous fat; the fat that is visible just under the skin. Visceral fat lies deep within the abdominal cavity, padding the spaces between the abdominal organs. It is a highly active tissue that has metabolic, endocrine, and immune functions. Abdominal fat has been linked to metabolic disturbances and increased risk for cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes[7] and Alzheimer’s disease. In women, it is also associated with breast cancer.[8]

Fortunately, visceral fat capitulates fairly easily to exercise and diet and this is where Fitness Professionals can have a positive impact. Lifestyle interventions such as exercise and diet resulting in weight loss and loss of visceral fat can have a significant impact on lessoning cardiometabolic risk.[9]

What Else Happens When the Parasympathetic Nervous System Doesn’t Activate Properly?

With prolonged, chronic, low-level stress, however—the type of stress many people endure for weeks, months, or even years—the HPA axis remains activated. This has an effect on the body that contributes to the health problems associated with chronic stress and can impact your client’s ability to lose weight.

- Loss of sleep: adrenaline can increase insomnia, and incudes having a hard time getting to sleep or staying asleep. Sleep is when, among other things, the body repairs itself, protects from illnesses and balances hormone regulation such cortisol, ghrelin and leptin, which can factor into weight gain. Lack of sleep can also affect cognitive brain function and the choices that we make, including for diet and exercise.

- Effects in the brain and other organs: recent studies have shown prolonged surges of adrenaline can damage blood vessels, including those in the brain, and increase risk for developing headaches and anxiety. The damage to blood vessels can also increase blood pressure and elevate risks for heart attack and stroke.

- Impaired digestion: For good digestion to occur, the parasympathetic nervous system must be activated. Therefore, good digestion cannot take place when the body is under stress! Stress can slow contractions in the digestive tract (which slows transit time of food), and shunt blood away from the digestive tract and to the extremities in preparation for flight. These two reactions alone can have a huge impact on the body’s ability to absorb nutrition properly and can lead to cravings as your body is craving needed nutrients.

How can Nutrition Affect Stress Reduction for Your Client?

Nutrition plays a significant role in how the body reacts and responds to stress. Why do some people overeat when they’re feeling stressed or anxious? The gut helps regulate appetite by telling the brain when its time to stop eating. About 20 minutes after eating, gut microbes in the microbiome, produce proteins that can suppress appetite, which coincides with the time it often takes to begin to feel full. Stress can disrupt these signals, causing eating to continue, even when full, or to eat without awareness (mindless eating). Adopting a healthy eating style that includes whole, natural, nutritious foods can help support your clients’ goals for weight loss and reduce stress. Some of the nutrients that have been shown to help reduce stress are listed below.

Nutrients that Help the Body Manage Stress

Stress can slow down the digestive process, increase inflammation, and interfere with sleep. It can also affect how nutrients are absorbed, used, and stored, leading to symptoms such as fatigue, mood disturbances, and muscle pain (which can affect recovery time) and of course weight gain.

Specific nutrients that are required in the stress response are:

B Vitamins

The B vitamins perform a variety of roles in the body, including supporting the nervous system and helping to produce neurotransmitters like serotonin, which enhances mood and better enables the body to relax and sleep in times of stress.

The B vitamins perform a variety of roles in the body, including supporting the nervous system and helping to produce neurotransmitters like serotonin, which enhances mood and better enables the body to relax and sleep in times of stress.

Dietary sources of the B vitamins include whole grain foods, raw dark leafy greens (for example, spinach and kale), sunflower seeds, almonds, avocados, bananas, and sweet potatoes. During periods of stress and for chronic stress, daily supplementation with a B complex vitamin (sometimes labelled ‘stress formula’) is helpful. B vitamins may increase energy and should be taken early in the day with food. Avoid taking B vitamin supplements near bedtime.

Magnesium

Most people consume insufficient amounts of magnesium—a mineral needed for more than 300 biochemical reactions in the human body. Magnesium controls the activity of the HPA axis—the body’s stress-response system.[10] Low levels of magnesium are associated with increased stress, anxiety, a poor mood, and muscle tension. Magnesium increases levels of GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), a neurotransmitter that encourages relaxation and sleep and helps reduce feelings of anxiety and fear.

Dietary sources of magnesium include green leafy vegetables (spinach and kale), wholegrain foods, nuts, seeds, bananas, figs and raspberries, and dark chocolate.

Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid)

The antioxidant Vitamin C is involved in anxiety, stress, depression, fatigue and mood in humans.[11] The body stores a limited amount of Vitamin C in the adrenal gland. During the stress response, the vitamin is rapidly used to produce cortisol and related hormones. People with higher blood levels of Vitamin C recover from the effects of stress faster than those with lower levels.

The antioxidant Vitamin C is involved in anxiety, stress, depression, fatigue and mood in humans.[11] The body stores a limited amount of Vitamin C in the adrenal gland. During the stress response, the vitamin is rapidly used to produce cortisol and related hormones. People with higher blood levels of Vitamin C recover from the effects of stress faster than those with lower levels.

Dietary sources of Vitamin C include fresh uncooked fruits and vegetables, especially citrus fruits, kiwi, and red peppers.

The B vitamins, magnesium and Vitamin C are all water-soluble, so are generally not stored in the body. Eat foods that are rich in these nutrients throughout the day to ensure sufficient intake of them. During periods of chronic stress, take a daily supplement (e.g., stress formula).

Consider These Factors for Reducing Your Clients Stress Levels and Their Weight

Stress has been demonstrated to influence weight gain. Stress can also be mitigated by whole-body lifestyle interventions such as proper exercise, sleep, and diet. Make sure to consider the following factors when working with your clients:

- Proper exercise: Exercise can also be a stressor on the body. Including adequate rest and recovery days and modifying exercise programs to include mind/body exercise such as tai chi, yoga, breath work, stretching and other modalities that will help reduce stress, can be helpful.

- Sleep: Recommend sleep hygiene suggestions, for example reducing screen time and using a blue light filter on electronics.

- Diet: What your clients eat can be crucial to their overall wellness and the successful achievement of their goals. What they eat not only affects their short-term outcomes such as weight loss but can influence their overall health throughout the rest of their lives. Adopting a healthy eating style with natural, whole foods will not only help in their efforts to reduce stress, but it will also support their goals for weight loss as well. Having the client keep a food, mood and activity journal can provide helpful insights.

How to Talk to Your Clients About Stress!

Unlike Fitness Professionals, your clients don’t need to understand the mechanisms behind the fight or flight response and the HPA axis. But they should have a general understanding of how stress can impact their weight and overall health, and why its important to address it. Here is a simple explanation to share:

Stress can put your body into fight or flight mode, which is your body’s way to prepare for facing danger. When you are stressed, adrenaline is released into your bloodstream and that gives you extra energy in case you need to run or fight, hence they call it the “fight or flight” response. The problem is that your body doesn’t differentiate between a man-eating tiger chasing you or a traffic jam or a work deadline. If we are constantly under stress, producing adrenaline, it can actually cause issues in our body. For example, we might have trouble sleeping, have issues with our digestion and even with cognitive function and memory. Stress causes us to produce a hormone called cortisol which increases the body fat around our middle and makes it harder to lose weight. That fat around the middle can increase risk for lots of chronic illnesses and diseases such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. So, dealing with stress will not only be good for your goals of losing weight, but also your long-term wellness. And here are some simple ways that you can manage stress: diet, sleep, exercise etc.

To learn more about transforming lives using a whole-body approach, click here for the Free Preview of the Natural Nutrition Coach® Certificate Program. The Preview includes the first Section of our Nutrition Module and a Food Journal Template that you can download and keep, to use for yourself or with your clients!

To learn more about transforming lives using a whole-body approach, click here for the Free Preview of the Natural Nutrition Coach® Certificate Program. The Preview includes the first Section of our Nutrition Module and a Food Journal Template that you can download and keep, to use for yourself or with your clients!

Lisa Tsakos, R.H.N. is a nationally recognized holistic nutritionist, educator and author specializing in weight management and corporate nutrition programs. Lisa is a co-author of the Natural Nutrition Coach® program

Heather Creamer R.H.N. is the Chief Operating Officer of MedeXN Fitness Institute (www.medexn.com )and co-author of the Natural Nutrition Coach® Certificate program.

References

(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4296439/#ref1

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4214609/

[3] https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response

[4] Psychological Stress and the Autonomic Nervous System – ScienceDirect

[5] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs13679-018-0306-y

[6] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00217-016-2772-3

[7] Tsakos, Lisa, R.H.N., “The Weight Battlefield, A Holistic Approach to Weight Management, Second Edition.”

[8] “Abdominal fat and what to do about it.” Harvard Health. Sept. 2016. Web. Available from: http://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/abdominal-fat-and-what-to-do-about-it

[9] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1559827609360959